Book Review

Riding with Reindeer: A Bicycle Odyssey through Finland, Lapland, and Arctic Norway

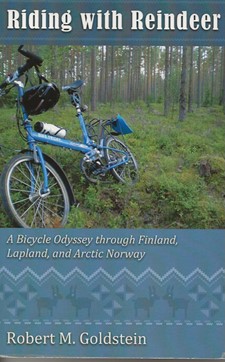

Riding with Reindeer: A Bicycle Odyssey through Finland, Lapland, and Arctic Norway

by Robert M. Goldstein

(Rivendell Publishing Northwest, 2010, xiv, 337 pp.)

An escape plan so that he could live again

In 2005, Robert Goldstein was fifty-one years old and in his sixth year of a high-stress job in Seattle. He felt like a prisoner, and his friends told him that he looked exhausted and haggard. He concluded that if he were to stay with his high-paying job he would soon be dead. “The trade-off seemed like a no-brainer: be free or work a few more years at a job I had come to hate. If I continued on the latter track, I believed I would soon drop dead” (p. 5).

He concocted an escape plan, to spend a summer bicycling across Finland, on a circuitous route that would take him from the southernmost to the northernmost extremities of this strange little country wedged between Norway and Sweden on the west and Russia on the east. He had started bicycling when he was given a new bicycle for his seventh birthday. Ten years later he and a cousin had spent five days bicycling from his home in Santa Clara, California, to the Russian River. He kept on riding, using his bicycle for pleasure and basic transportation. In 1982 he toured China by bicycle and 19 years later he biked from Nanking, China, to Hanoi. Somewhere along the way he spent time cycling in southern Arizona with the PAC Tour Desert Training Camp, with coaching by Fred Matheny, one of the experts in doing long, challenging bicycle tours. ✎

In 1987, when he was thirty-two years old, Goldstein made what he describes as “a dubious solo trip across the Soviet Union aboard the Trans-Siberian Express.” He later wrote a book about the journey, published in 2005 with the title The Gentleman from Finland: Adventures on the Trans-Siberian Express. He had been given this identification because his visa that allowed him to make this journey had been issued in Helsinki. Another connection with Finland was the knowledge that “a long-lost great-grandmother” lived in Helsinki be-fore leaving as a young woman, probably hoping to find a husband in the Russian Empire’s Jewish Pale of Settlement (p. 4). Goldstein’s interest in Finland was also stimulated by stories of Finnish bravery during World War II and accounts of the cultural and political achievements in later years by the people of this unique country on the edge of Europe.

The solo expedition he planned would be the longest he had made, about 2,000 miles in length. Much of the detail, however, would be developed day by day as he traveled. His intention was to make fifty miles per day his limit and to take a day or two to rest every four or five days. He took everything he needed for tent camping and doing his own cooking, but he presumed that he would also take advantage of other kinds of camping opportunities as they came along. His budget was tight ($70 per day for a two-month trip), which meant that he had to find ways of avoiding large costs such as flying a regular bicycle to Europe. What saved him this expense was the opportunity to buy a used Bike Friday, a folding bicycle with small wheels and frame that packed in a suitcase and traveled as regular baggage. When outfitted with tongue and lawn-mower wheels, the travel case could be towed as a wagon to carry his gear.

You know it is a very long way to Lapland

When he arrived at the Helsinki hostel to begin his journey, Goldstein’s shuttle driver wished him well on his travels, commenting “You know it is a very long way to Lapland.” Goldstein already knew that it was a long way but admits that hearing it “from the mouth of a native Finn, it seems even longer” (p. 8). A challenge facing travel writers is to describe their journeys so that people who hear or read the narrative experience how things look and feel, especially as they are conditioned by the cyclist’s mode of travel and range of interests. Driving through desolate mountainous terrain with gas in the car and protection from violent rainstorms is significantly different from cycling in those same conditions, risking hypothermia and hunger. For all travelers, their personal interests—the terrain itself with its flora and fauna, the human history and continuing culture, the towns and cities and the built environment—shape their experiences and the stories they tell about it.

Goldstein’s interests were already shaped as he began his journey, but my sense of the book is that he became increasingly focused upon the geographical and cultural intersection of Finnish and Sami life and culture. This aspect of his narrative is especially interesting to me and my siblings because our mother’s family heritage is Finnish. Although she was born in the United States, her parents were immigrants. She grew up in a household and community in which Finnish was widely spoken and probably was her first language.

As a long-distance cycle-tourist myself, who visits museums and reads books about the history and culture of places through which I ride, I appreciate Goldstein’s skill in interweaving similar elements in his developing narrative. Early in his trip he summarizes the work of Carl Gustaf Mannerheim, the military hero whom he describes as the father of modern Fin-land, and Jean Sibelius, who “claims that title in the realm of classical music” (p. 32). A little later in the ride, in a chapter entitled “Lenin Slept Here,” he summarizes Lenin’s unsuccessful efforts to bring Finland into the Bolshevik movement. Cycling through Finland’s lake country, he summarizes the work and impact of Finland’s “most famous architect,” Alvar Aalto. At travel points where he finds artifacts remaining from the nation’s involvement in World War II, Goldstein calls attention to the courage and remarkable military skill of Finnish forces during that terrible time.

As he draws near the halfway point of his journey, Goldstein feels a cold coming on and decides to check into an inexpensive hotel in Kuopio, a city of 91,000 people, in order to convalesce. While there, he decides to follow local advice and take a smoke sauna at the edge of town at what “is reputedly the world’s largest smoke sauna.” He describes the experience in considerable detail and concludes that it seems to have cured his cold. He continues his journey into North Karelia, which he describes as culturally distinct from the rest of Finland and “the haunt of Finland’s folk heroes, who manifest themselves in the Finnish epic poem the Kalevala” (p. 153). Along the way, he stops at one of the first battle fields “of the horrible Winter War” in which Finland’s vastly outnumbered military force was able to over-come Russian invaders. Although I was only eight years old when that war took place, I was fully aware of my Finnish ancestry and felt a strong sense of identify with and pride in their bold achievement that was frequently reported on radio news accounts.

Goldstein decides to lay over in the city of Kuhmo, “the last city of decent size before I wobble into the forests of North Karelia” (p. 162). There he learns about bears and wolves, and the potential dangers they pose, but perhaps more unsettling is the description of the gulo gulo, that is “very rare, but fierce,” and might be encountered when someone is wandering in the forest at night. The description given him by a knowledgeable guide reminds Goldstein of the Sasquatch figure or the Jabberwocky in Lewis Carrol’s poem. The agent suggests that he carry a gun, but he doesn’t follow her counsel. This conversation and the general spookiness of the lonely woods through which he is traveling unnerve him, however, especially during the night that he describes in the chapter entitled “The Haunted Cabin.” At this point in the narrative, Goldstein begins to encounter reindeer, which leads him to de-scribe the animals and their patterns of life. He explains how many Finnish and Sami residents of the northern regions of the country depend upon these large, semi-wild animals that they herd during portions of their annual migrations.

During his layover in the city of Kupio, he also takes time to improve upon the emergency repair on his wagon that he had made much earlier in the trip when one of the wheels had fallen off because of the rough pavement on which they were travelling. One of the positive features of the journey is how well his bicycle and wagon perform. The equipment failure that plagued him, especially as he cycled through regions heavily infested with mosquitoes and other vicious flying creatures, was his tent. With duct tape from his own supplies, and clothes pins found along the way, he keeps it tight enough to keep some of them from penetrating his nighttime shelter.

Back on the road after his layover in Kupio, Goldstein planned to ride about 132 miles in three days to the city of Rovaniemi and his rendezvous with the Arctic Circle. This part of the trip is more challenging than he had anticipated. His planned first day of an easy forty miles begins “almost effortlessly.” Arriving at the campground with much of the day remaining, he decides to press onward. Along the way, a giant inflatable snowman greets him at the spot where the road crosses the Circle. He reports conversations in coffee shops and at monuments along the way. At the campground where he finally ends the day, he talks with a trio of pannier-laden bicyclists—a young man and two older men—who had started their trip in the northern-most town in Arctic Finland.

As was true for most younger Finns whom Goldstein met, the young man (Timo) spoke fluent English. Since he depends upon English, a Finnish-English phrase book, and sign language to communicate with people, Goldstein takes full advantage of the opportunity. “When I tell him my ultimate destination, he puts his hand on my shoulder and says, ‘This is fantastic, but I must tell you about Lapland. It is a hard journey. There are many big hills’” (p. 215). As were other cyclists he had seen, these men were riding north-to-south, which made sense because that was the direction of the prevailing winds. The next morning, he hears more unsettling news: “The road is very bad. Lots of potholes . . . And the fells, they are horrible. We call them the ‘Hills of Bicycle Death’ because the mosquitoes will swarm up and at-tack you as you struggle up the hills” (p. 217). Although Goldstein is little troubled by wind during the thirty-seven-mile final day to Rovaniemi, he does struggle with temperature in the high seventies, finding it ironic that the farther north he traveled, the warmer it was get-ting. A happy surprise is to find that Timo, now with a girlfriend instead of the older men, is also staying in the city because his bike needs serious repairs.

Later that day Goldstein cycles a few miles out of town to visit Santa Claus Park, discovering that even in the off-season it is a very busy place. His sour response to this highly commercialized place is characterized by his comments. “I need fresh air,” he writes. “The absence of Santa, the discovery of the long-lost euro cent, and the spiraling tower of Babel is all a bit overwhelming. Perhaps I’ll have a word with Santa’s reindeer, I decide. They’re no doubt pastured nearby grazing for the big madcap ride in December.” He’s disappointed at what he finds, a sign at a shop nearby advertising the special of the day, “Smoked Salmon and Reindeer.” Another shop “sells T-shirts emblazoned with ‘Good girls go to heaven. Bad girls go to Lapland’” (p. 230).

Just keep moving, I tell myself

During his three days in Rovaniemi, “the last city of any significance” our traveler would encounter while traveling through the final section of his expedition, he rests, visits interesting sites, repairs his equipment, restocks his supplies, and probably checks email at a library. He also studies maps, trying to discern which roads to take in this increasingly desolate part of the world that was already beginning its preparations for winter. He notes that Lapland is the “most sparsely populated area of Europe” and that 65,000 of its 85,000 residents are native Sami people who are “scattered amongst the vast stretches of reindeer-wandering open space and in the small villages” he would pass through during the next week (p. 232). He al-so refers briefly to other travelers who have written about their travels in Lapland, including the Swedish scientist Carl Linnaeus who rode across that land by horseback in the early 1700s.

On the road again, he continues through this solitary land, sometimes having trouble finding campsites, reverting on occasion to sign language to indicate what he wants with people who speak only Sami. Even here, he encounters other cyclists, this time a German couple who give him discouraging reports about conditions ahead. At one point, the succession of steep hills, painful twitches in his left knee, and wasps stinging his upper body force him to dismount and walk up the hills, musing that Timo “wasn’t kidding about the Hills of Bicycle Death” (p. 265). He finds respite in a cabin near the community of Inari, with its population of five hundred and fifty, and prepares himself for the final portion of the expedition, which was to reach the northernmost point of Finland. Although the Expedition would there be completed, he would then cycle into Norway and ride to the Barents Sea, as close to the Arctic Ocean as he would go. As had often happened earlier in the journey, he has to contend with intense storms that drench him during the day and make nights in his tent difficult to endure.

The maps and road signs, however, continue to baffle him. After one set of markers indicate he had reached the northern tip of Finland, he discovers another road pointing ever further north. At one point, he must push his bike up a fifteen-percent grade, slipping and sliding on the muddy slope. At its crest, two big reindeer bulls, each with two sets of antlers, stand like “sentinels in the middle of the road” (p. 282). At the village of Nuorgam, he sees another sign declaring that he is at the northernmost point and not wanting to take a chance that he would miss the real place takes another set of photos. He rents the northernmost cabin and buys food appropriate for the northernmost meal. Soon after eating and celebrating with a bottle of northernmost beer, he writes, “I crawl into my bunk and sleep like someone who has biked the length and width of Finland for the past forty-one days, while outside yet another rainstorm of Biblical proportions begins to rage” (p. 283).

Instead of turning south, however, traveling to the closest place where he and his bike and wagon could board motorized transit for the return to Helsinki, he continues his northerly ride into Norway, to the town of Kirkenes on the Barents Sea. He then travels by ferry around the northern section of Norway to Hammerfest, “which bills itself as the northern-most incorporated city in the world” (p. 304). He continues southward through another section of Norway by motor coach, and then becomes a cyclist again for two more days (105 miles), to the town of Sirkka where he would take the train for the long ride back to Helsinki. The minibus rides take him through Sami country, which provide Goldstein with opportunities for extended conversations with Sami people whom he meets as fellow passengers. A Sami woman driving one of the buses asks him about his bicycle trip. After she relays the highlights to her Sami friend who is one of the passengers, she tells him that he is “like an old Sami because you like to move every day from one camp to another. . . And you’re short, too. You just need some reindeer and a Sami wife” (p. 313).

During his final ten miles with the conversation partners he appointed to accompany him—Friday, Wagon, and Body Parts of Bob—Goldstein writes that he is “vaguely aware” that his “epic journey is over” and that he has lived to tell the tale, riding over 2,100 miles, and “accomplished what I set out to do, both physically and mentally. I have removed myself from everyday life and had an adventure.” When starting the trip, he had “dreamt of sprinting the last few miles in one final adrenal celebratory rush,” but he could not. Both body and brain were worn out. “What thoughts I have are fragments, and these are short-circuited by blankness. I have achieved a Zen state, but not through practiced meditation but by exhaustion. I see, but I don’t think” (pp. 321-2).

After his return to Seattle, Goldstein did not return to what he describes as “the nine-to-five routine of the work world,” instead accepting a part-time position. Once a week he rode his road bike (Friday was resting) eleven miles, took an hour-long ferry ride, and climbed “some mean fell-like hills—but after completing my Finnish epic—a trip I now sometimes have trouble believing I actually did—nothing much fazes me anymore” (p. 326).

Although I have taken long, bike trips, one even longer than this ride through Finland, none of them compares with Goldstein’s expedition. Mine have been in English-speaking North America, using networks of paved roads, traveling through populated territories. During most of them, I have depended solely upon nightly lodging in public accommodations (although on a few occasions I have come close to having to find some kind of make-do provisions). I have written extended descriptions of my travels and read many others. Clearly Goldstein is an accomplished cyclist, fully prepared for this trip, and highly skilled in describing the physical, emotional, cultural, and historical character of his remarkable summer. Many photos and four maps help readers follow the journey he describes. Even so, I some-times had trouble following the itinerary and would have appreciated a more detailed itinerary of the trip he describes.

My conclusion can be stated quite simply: Riding with Reindeer is one of the best bicycle travel books written in recent years. It will be interesting and illuminating both to hard-core cyclists like me and to other readers also interested in ways that personal travel inter-sects with the built world and cultural experience.

My email address is [email protected], in case you want to contact me.

Keith Watkins, Guest Contributor