Safety: The Gap Effect

The gap is brutal. It was just such a situation that got me hit by a car in July of 2006. I was proceeding downhill on Barbur Blvd at about 25 mph heading into downtown. There are seven lanes in this stretch (near the Original House of Pancakes) – two car travel lanes and one bike lane in each direction, and a two-way left turn lane. A car in the left turn lane saw the gap in traffic but didn’t see me. It cost $800 to get me to the Emergency Room and $4,000 more to get me out. And I wasn’t even hurt that badly, just some badly bruised feet and lower legs and 17 stitches in my left hand. But my helmet did its work!

The gap is brutal. It was just such a situation that got me hit by a car in July of 2006. I was proceeding downhill on Barbur Blvd at about 25 mph heading into downtown. There are seven lanes in this stretch (near the Original House of Pancakes) – two car travel lanes and one bike lane in each direction, and a two-way left turn lane. A car in the left turn lane saw the gap in traffic but didn’t see me. It cost $800 to get me to the Emergency Room and $4,000 more to get me out. And I wasn’t even hurt that badly, just some badly bruised feet and lower legs and 17 stitches in my left hand. But my helmet did its work!

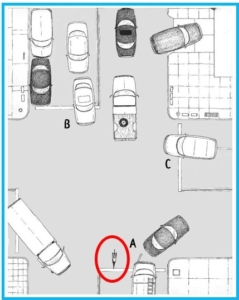

Photo: While riding in a proper position in the street, to the left of the right turners (A), this cyclist is nonetheless entering the intersection at a dangerous time. The light has just turned yellow, and an illusory gap has appeared in the traffic. As she rolls through, the rider will be at the mercy of two impatient drivers: the left turner (B) and the right turner (C), both looking to shoot the gap.

I have received permission from Ryan Meyer of Globe Publishing to use the excerpt below from Robert Hurst’s book The Art of Cycling (previously published as The Art of Urban Cycling). We have both books in the PBC library collection. I believe the book has some very useful tips:

THE GAP EFFECT

Mind the gap. The gap is brutal.

Consider the condition of some of the drivers locked in the typical traffic grid. They’re trying to make a left turn, but all they see is an unbroken line of fast-moving vehicles coming at them, with no end in sight. They’re late. They’re hopped up on four cups of coffee. They’re about to pee their pants. They’ve been waiting to make that left turn since the Mesozoic era. Actually, they’ve been waiting about thirty seconds or so, but to them it seems like a very long time. Like the dinosaurs of the Mesozoic era, their eyes are bigger than their brains. Suddenly a small gap opens in oncoming traffic. They’re going to hit that gap if it’s the last thing they do, which it may very well be. They stomp on the gas and crank the wheel. This is the Gap Effect in action.

One big problem, though: There’s a cyclist in the gap, puttering along. The motorist doesn’t notice or perhaps, so in love with the idea of the gap, simply denies the existence of anything that could possibly spoil this golden opportunity. In any case the cyclist is going to get hit, badly, unless he or she can flash some serious evasive maneuvers. In this way the dreaded gap is often a factor in the kinds of statistically overabundant car-versus-bike incidents that claim very experienced, streetwise cyclists—the wrecks where the motorist turns left into or pulls out in front of someone on a bike.

As a bike rider in the city, it is nearly impossible to avoid riding in dangerous gaps around intersections. Too many gaps, too many intersections. The best way to avoid gap disasters is through recognition and anticipation. The Gap Effect is one of the best reasons to remain on high alert in traffic. Don’t just mosey along out there. Recognize that a gap exists, your position in relation to it, and the presence of vehicles that might want to blast through it, from the left and right. If your view of any potential gap shooters is blocked, their view of you is also blocked. Assume they are there with their clodhoppers poised over the gas pedal.

Old hands who have had bad experiences in the gap develop an instinct for gaps and some very cautious techniques to solve them. Rather than occupying a gap through an intersection, the rider might jump forward to hug the space of the car in front a bit and hang about six or eight feet off its right rear, to use the car as a sort of shield against crossing traffic. Keep in mind that the blocking vehicle itself could become a hazard if its driver decides to turn or stop suddenly.

Dave McQuery, Club Member

______

Hurst, R. (2007). The Art of Cycling, pp. 94-96, Globe Publishing.